This is my friend’s lovely cat who died recently.

From the Club page of Forget-Me-Not magazine, “A Dainty Journal for Ladies”, 27th August 1910. Good novel material, sounds like the start of an Oxenham book:

I wonder whether any of our members would like to give 26682 (Trowbridge) a holiday under the terms she mentions? Here is her letter:

“I hope you will not think I am wanting favours too soon,” she writes, “as I am a nearly new member; but I have been reading some of the wants of our members, and I wonder whether someone could do with me for a week. I am a good amateur dress-maker, and can do almost anything in the way of household duties; my mother had both us girls taught all that kind of thing, and I could be very useful for a few days to anyone who was nice to me. I am thoroughly healthy, and happy natured, and I would not give one bit of trouble, but I do so want a holiday! I can keep accounts, or make myself useful in lots of ways, and I would work all morning if they would give me the afternoons and evenings. I should like it to be not very far off, and seaside if possible; we have a nice large house here, and could have someone back here later on if they would like to come; try to do something for me if you can. I am educated fairly and all that, you know; no one need be afraid to have me; and I am sure I can pay well by my work for my food for the time!”

There are some class-markers I think in “my mother had both us girls taught all that kind of thing”, as well as the more obvious statements about the “nice large house” and education.

Memoir by Rebecca Stott, 2017.

Guardian review here.

There is a description of Stott illicitly discovering Enid Blyton in the school library:

The library door was open. That, I persuaded myself, probably meant it was all right. The Lord must be showing me the way …

On the cover of The Secret Island, a group of children a few years older than me crouched on a clifftop looking down on a sandy beach where some suspicious-looking grown-ups were unloading a rowing boat. The children looked as if they were in danger, but they also seemed to know what they were doing. …

I read as if turned to stone, breathing in the musty smell of the book, my bare knees marked by the edges of the floorboards. Before this I had only read the Janet and John books with my mother: John is in the tree. Janet is in the kitchen. And the Bible, of course. I had read most of it by now, aloud, kneeling on the floor of my parents’ bedroom. But there were very few stories about children in the Bible …

Why was Nora crying in the field? …

When the bell rang ten minutes later, I stuffed the book underneath a dusty red beanbag in the corner. Brethren children were not allowed to borrow library books. I would have to hide it so no one else could borrow it before I came back.

Where had the children’s parents disappeared to?

Could Jack be trusted? …

Jack now occupied the place in my head where only God and my parents had been before. He was on the right, and they were on the left. It was easier to keep them in separate rooms. I negotiated with God, but sought advice and good sense from Jack. I agreed with Jack when he told the others that sometimes grown-ups could be cruel, unfair and plain wrong. … He always knew what to do. He’d know what to do when the Tribulation came.

There’s also a good bit, as long as one holds in one’s head that the kittens are ok, where the writer visits a friend and kittens in silk parachutes drop down from the facade of the house as she arrives. They land safely and are unperturbed apparently. Later on she worries that she should stop seeing the friend as they are Catholics, but more kittens are expected (not by parachute) so she doesn’t.

Katha Pollitt, 2007.

I hadn’t previously heard of this American theorist and essayist. Came across this book through a Slate problem page question, where it is recommended to someone who doesn’t drive. It’s not really about that, but I’m glad I read it anyway. Some quotations:

Talking about what a world without men would be like, which made me think about my mother’s relationship with her husband, my stepfather:

Will it be restful, not having to think about love, romance, sex, pleasing, listening, encouraging, smiling at the old jokes – all the small ways and not so small ways women bend themselves to men’s expectations, needs, habits, antennae always raised as if for sounds from the baby’s room? Men take a lot of attending to and on; there’s a lot of putting down of books involved, a lot of turning down of radio just when a story comes on you really want to hear, to say nothing of the day turning into one meal after another. A can of soup is never enough somehow; before you know it you’re ordering huge quantities of Chinese food. It would be nice to think that when one has gotten used to it, it will feel like a well-deserved retirement. “Barbara has a woman friend she goes on trips with,” I heard one white-haired woman tell another at a classical music concert at our local church. “And this friend said, ‘Barbara, between us we’ve had five husbands and they’re all gone.'” And the two old ladies, trim in their good suits and pearls, shrugged their shoulders and laughed.

She writes about her parents. This is her father, a lawyer and Communist Party member:

He knew the words to hundreds of forgotten popular songs – “My Gal’s a Corker,” “I Had a Hat When I Came In,” “A Bird in a Gilded Cage,” – and all the verses of “Ivan Skavinsky Skivar.” He called Italians eye-ties and wops and dagos. He told me not to become a lawyer because the law was coarsening. He told me men are the makers of civilization and women are its bearers. He woke me for school every morning with a quatrain from the Rubáiyát – “Wake! For the Sun, who scatter’d into flight / The Stars before him from the Field of Night / Drives Night along with them from Heav’n, and strikes / The Sultan’s Turret with a Shaft of Light.” This never failed to irritate me, but now I wonder if any child on earth is roused from sleep like that. After my mother died he turned my bedroom into an off-the-books bed-and-breakfast and, despite being an atheist, prominently displayed on my old bureau a framed biblical verse in needlepoint about entertaining angels unawares. … He even, in the end, made money, like a lot of Communists. All those years of scrutinizing the economy for signs of imminent collapse taught them something. He was eighty when he told me, “Basically I wake up every day with a song in my heart.”

In the title essay, Pollitt describes her driving instructor’s analogy of driving to “making beef stew”. “‘you taste it. So: what do you do when you’ve lost track of which way the car is pointing when you parallel-park? … You just let the car move back a tiny bit and see which way it goes! You taste the direction!'”. She talks about her poor observation skills and how this affects her driving lessons and her failure to notice her partner is having an affair. This essay is online at NPR. It was also turned into a film.

About her mother, who died of the damage caused by alcoholism when she was 54:

[She] had majored in journalism, and had even worked briefly at the Daily News writing picture captions for the sports page. But the only published work I ever saw of hers was – maybe – the anonymous entry for Richard III in the Columbia Encyclopedia, where she had a temp job as a researcher. She told me she had tried to subtly inveigle into the dry language her sympathy for Richard, history’s underdog, and sometimes when I read that entry over I can see a ghostly effect. “Some historians have maintained that Shakspere’s interpretation of Richard is unjust but the impression remains.” “Unjust” sounds so like her. Mostly she transferred her ambitions to me … “

Pollitt writes about her own fingers “horrifying” her as a teenager as they were so similar to her mother’s (something with which I can identify), and how her perspective has changed. “I like to think about the echoes of them [her ancestors], and of me, in my daughter’s face, and the unexplained folds and angles that remind us that we are all made up of recombined bits of ancient ancestors, even if we don’t know who they are. The precise pattern of your wrinkles might be the only one on earth that matches that of a Sumerian farmer who raised millet and goats around 3000 BC. I like to think of him, relaxing with a pot of his wife’s home brew and looking up at the stars”.

Isabella Alden, “Pansy”, 1888.

Ruth Erskine is not the most immediately appealing of the four girls who go to Chautauqua in the first book of the series. Compared to Flossy, who is child-like, warm, empathetic and “impresses me as one who is being led” (Ester Reid Yet Speaking), or Marian, clever, poor, proud and ambitious, Ruth’s focus on respectability and her cold self-control are at times almost repellent. She has difficulty finding joy in religion, and is told “Joy is one of the fruits that you are commanded to bear” (Ruth Erskine’s Crosses).

Ruth is plagued by unsuspected and unwelcome family-by-marriage appearing in her life. After her father, following her example, has found God, he tells her that he married again years ago, following the death of Ruth’s mother. He then realised that his new wife “was ignorant, uncultured, and, it seemed to me, unendurable” (The Chautauqua Girls at Home), and pays her to take their daughter and go away. Now having religious convictions, he brings his wife and daughter home, causing Ruth “horror” (Ruth Erskine’s Crosses). Once Ruth herself is engaged, her fiancé reveals that he was married before and has two daughters, Seraphina and Araminta, “their very names a source of mortification to me … Their mother was a hopeless victim to fourth-rate sensation novels, and named her daughters from that standpoint”. He tells her

These girls are not like your class of girls. They have no interest in refined pursuits. They have no refinement of feeling or manner. They have no desire for education. They do not even care to keep their persons in ordinarily tasteful attire. They care nothing for the refinements of home. They belong to a lower order of being. It is simply impossible to conceive of them as my children.Ruth knows it is her duty to care for his daughters and to try to civilise them, and bring them to God, so takes them into her house as her father had brought his wife and other daughter home. When Ruth Erskine’s Son begins, Alden has culled Ruth’s family pretty heavily – her father, husband and step-daughters are dead, and her step-sister has gone as a missionary to China. “It seemed to [Ruth], looking back, that her chief mission in life had been to minister at dying beds and follow as chief or almost chief mourner in funeral processions.” She is alone with her son, Erskine, who is 17 at the start of the book. I was particularly interested in the way in which Alden shows Ruth following her son’s academic and professional career.

Mrs. Burnham, finding much time at her disposal, proposed to Erskine that she take up some of her long-ago-dropped studies and let him introduce her to modern college ways. The young man laughed as he gave her an admiring glance and assured her that she knew more than other women, already. Nevertheless it pleased him to go into careful detail about his work, and on the following day it surprised as well as pleased him to find that his mother was quite as well prepared with some of his studies as he was himself. From that evening a new order of things was established; Mrs. Burnham, without matriculating as a college student, and without letting it be known, save to the choice few who were their very intimate friends, became nevertheless a student. How much of Erskine Burnham’s acknowledged success in college was due to the fact that his mother studied with him throughout the entire course is something that will never be known; but her son gave her full credit for the help that she was to him. From the first he recognized her as a stimulant; he discovered that he must have his points very fully in his grasp in order to explain them satisfactorily to his pupil. She always insisted on being his pupil and kept carefully the subordinate place, although her keen questionings more than once led him to change his view of a subject under discussion.

Once Erskine has become a lawyer, we are told that

She had not kept up with his legal studies as she had almost done through his college course, but she had kept in touch with them, and could copy his notes for him, giving him just the points he needed — better, he told her, than he could do it himself. “We will take you into the firm if you say so, dearest,” he said gayly one evening, after a spirited argument between them with regard to a point of law in which Mrs. Burnham had vindicated her side by an appeal to an undoubted authority. “I told Judge Hallowell, yesterday, that it was easier to consult you than to look up a point, and did just as well. He would agree to the partnership, mother, without hesitation; he considers you a wonderful woman.” At which the happy mother laughed, and told him he was a wonderful flatterer; and then — Did he want her to look up the evidence in that Brainard case for him? She could do it as well as not. She had been reading up about it that morning.

This is really interestingly presented, I think. On the one hand Alden makes it very clear that Ruth’s understanding of law is better than her son’s; she is cleverer than he is. Although his response is patronising, it’s clear that he genuinely values his mother’s intellect and knowledge. She evidently enjoys both the work itself and helping him. There is no hint from the writer that she’s stepping out of a woman’s role. On the other hand, there is also no suggestion that Ruth is missing out by not being able to study openly or to use her own powers in a professional career. Because her son allows it, she is able to use her talents effectively; it is easy to envisage a version of the book where this would not be the case.

Back to Ruth’s mysteriously-appearing family-by-marriage trials. As a student, her son shows interest in a young woman, Mamie Parker. “Pretty, certainly, with a kind of garish, unfinished beauty, not unlike that of a pert doll … but what Erskine, her cultivated and always fastidious son, could find in the empty little brain to attract him was beyond the mother’s comprehension.” She makes vulgar remarks about young men, she doesn’t know how to use cutlery correctly and she sings poorly. Although Ruth prays about Mamie and tries to do the right thing, in fact she displays Mamie’s vulgarity to Erskine, who decides “she doesn’t belong”. A decade later, at thirty, he is apart from his mother for the first time, and returns home having married a woman called Irene. She is unkind to Ruth.

Irene has represented herself as a widow, but Mamie Parker then appears again and tells Ruth that this is not true. In the intervening years, Mamie has re-invented herself, partly as a result of what she saw of Ruth ten years ago. She has become a Christian, and tells Ruth “You gave me ideals, you refashioned my entire view of life; you were the means God used to breathe into me the spirit of real living … I had discovered from you what woman was meant to be”. She is about to go to China as a missionary, following her brother. It is hard for the reader, looking back, to accept Mamie’s statement about Ruth’s influence – it’s not clear that Ruth and Mamie had met more than twice, or that they had any kind of conversation touching on religion – but one of Alden’s recurring themes is the way we can have an effect on others even though we may barely know they exist.

Mamie tells Ruth that Irene was not widowed, but divorced, is ten years older than she has let Erskine believe, and that she had left her husband and baby daughter. Mamie assumes that Ruth knows this already, and her purpose is to try to interest Ruth in Irene’s daughter, whose father is dying. Ruth is deeply shocked by the information. Erskine does not believe in divorce, and has gone on record in his professional life that it is “unrighteous and infamous”. Throughout most of the book Alden emphasises Ruth’s self-control; this is the only point at which she breaks down with anyone else there, crying in front of Mamie. She wants to tell Erskine and to disgust him with his wife, but after prayer realises “She was to keep Irene’s secret, to suffer and to act in her stead; and to shield her son’s name and home as much as lay in her power. A miserable travesty of a home it looked to her; still, it was all he had, and for a time at least it could be kept sacred in Erskine’s eyes”.

Ruth does befriend and support Irene’s daughter, following the pattern established where she accepted her step-mother, step-sister and step-daughters as having a right to be part of the family. Irene is to some extent redeemed after she and Erskine have a son and she confesses her past to Ruth. She says that until she met Erskine, and later when she had the baby, she didn’t understand love. She had been disgusted by her daughter: “Even so early in her life she looked like him, and I hated him. He was a weak man, and I never had any patience with weakness. Sometimes he was maudlin and loving, and then I hated him worst of all”. She conveniently dies not long after her son is born. On Irene’s death, Ruth reminds Erskine of the question he had asked as a child when his father died, “does God sometimes make a mistake?” This, which had come to her as “a voice of tender reproof from God himself, and had helped her as nothing else did”, seems a harsh point to make (the point being of course that he doesn’t), but that harshness and pain is integral to Alden’s work.

Erskine marries Mamie, of course – she having come back from missionary work, finding that her brother doesn’t really want her there – and the book ends with a family of five: Ruth, Erskine, Mamie and the two children. This has been a lengthy coming together of people who have circled each other for years (Irene’s daughter was partly brought up by Mamie’s mother), with a lot of pain along the way for Ruth, for Irene’s daughter, and some for Mamie before her conversion. Erskine, despite his grief about Irene, perhaps comes off lightest, having been shielded throughout his life by Ruth. Alden writes that, of the four girls who went to Chautauqua, Ruth’s is the “the strangest, saddest story”.

In events other than reading, I have been thinking a lot about my own bitterness and regret over lost chances and talents not used, exacerbated by visiting my university. I do these mockeries of academic stuff, most of which are unfinished and pointless in any case (this blog being one of them), and it is hard to deal with the feelings around the things I have wasted and continue to waste.

Ngaio Marsh re-read: A Man Lay Dead (1934).

I’m doing a Marsh re-read in order, starting with A Man Lay Dead. The book is available online here. There are no spoilers in this review.

Setting

The setting is a country house belonging to Sir Hubert Handesley. The reader’s point of view is that of Nigel Bathgate, a young journalist on The Clarion. He has been invited for the weekend because his cousin, Charles Rankin, is a friend of Sir Hubert. The murder takes place whilst the characters are playing The Murder Game.

Number of deaths

One.

Love interest

Nigel Bathgate and Angela North, Sir Hubert’s niece. ‘”What’s all this?” thought Nigel confusedly. “I’ve only just met her. What’s happening?”‘ Later there is the rather revolting ‘Her hand felt cool and rather hard, but his lips persuaded it to be gentle’. They are wrapped in a ‘pink mist’.

Most irritating character

There is a lot of competition for this. Many of the characters are unpleasant.

Alleyn himself has an affected manner: ‘”You’ve guessed my boyish secret. I’ve been given a murder to solve — aren’t I a lucky little detective?”‘ and ‘”in the words of the popular coloured engraving, when did you last see Mr. Rankin?”‘.

Marjorie Wilde likes to make people feel awkward: ‘“We are leaving you Charles’s cousin,” she opened her eyes very pointedly at Nigel. “He’s a fine, clean-limbed young Britisher. Just your style, Angela.”’ She talks in a ‘comic opera’ style to the servant Vassily.

Rankin is a bully: ‘”Rankin bullied and goaded Wilde when they were at Eton. He showed a sort of contemptuous disregard for him in their later relations”‘. He’s also an annoying jokester (‘“Company…‘shun!” shouted Rankin’), a ‘philanderer’, and he’s rude and xenophobic towards Dr Tokareff.

Sir Hubert shows his class prejudice when talking to Alleyn: ‘”I see from your card,” he said courteously, “that your name is Roderick Alleyn. I was up at Oxford with a very brilliant man of that name. A relation perhaps?”‘

Nigel has an ingenuousness or childishness which can grate. On the railway journey, ‘”Who will be there?” asked Nigel, not for the first time’. We do hear in passing that he can be helpful and effective, but we mostly don’t see this directly, and it is difficult to reconcile with what we do see of him:

Nigel had been up all night, trying to get calls through to the family solicitor, to his own office, and, on behalf of the police, to Scotland Yard. He had been invaluable to Handesley and to Angela North, had succeeded in getting Tokareff to stop talking and go to bed, and had silenced Mrs. Wilde’s hysterics when her husband had thrown up his hands in despair and left her to it.

There is an unpleasant de-bagging scene:

“Let’s de-bag old Arthur,” suggested Rankin, emerging breathless from the hurly-burly. “Come on, Nigel…come on, Hubert.”

“There’s always something wrong with old Charles when he rags,” thought Nigel. But he held the protesting Wilde while his trousers were dragged off, and joined in the laugh when he stood pale and uncomfortable, clutching a hearthrug to his recreant limbs and blinking short-sightedly.

His glasses are broken and they laugh at his ‘silly little underpants’.

Angela is mostly less annoying and fairly direct. She puts Nigel in his place: ‘”Was that gallantry? It sounded like Charles.” Somehow he gathered that to sound like Charles was a mistake’.

Theatre / art / music

Nothing much here, except that the murder setting has a theatricality about it, and Dr Tokareff sings from Boris Godunov during the murder. Alleyn also mentions Eyes and No Eyes, a short musical by WS Gilbert and Thomas German Reed.

Alleyn’s character and appearance

The gentleman and “fastidious monk” aspects of Alleyn are established in this first book, as are the “right” people’s attitudes to him.

He looked like one of her Uncle Hubert’s friends, the sort that they knew would “do” for house-parties. He was very tall, and lean, his hair was dark, and his eyes grey with corners that turned down. They looked as if they would smile easily but his mouth didn’t. “His hands and his voice are grand,” thought Angela, and subconsciously she felt less miserable.

Rosamund puts this more crudely: ‘”This man Alleyn, with his distinguished presence and his cultured voice and what-not, is in the Edwardian manner. He hectors me with such haute noblesse it is quite an honour to be tortured”‘.

He has a ‘markedly Oxonian voice’, a ‘singularly charming smile’ and a knowledge of antiques. His flat has appeared in The Ideal Home. Nigel and Angela discuss him:

“Tell me,” she said in an engaging whisper, “do Chief Inspector Detectives usually invite the relatives and friends of the victim to dine in their flat, and do they invariably engage disappearing butlers as their own servants as soon as they are freed from arrest?”

“Perhaps it is The Thing Done in the Yard,” answered Nigel; “though, I must say, he doesn’t conform to my mental pictures of a sleuth-hound. I had an idea they lived privately amidst inlaid linoleums, aspidistras, and enlarged photographs of constabulary groups.”

“Taking a strong cuppa at six-thirty in their shirt sleeves. Well, pooh to us for a couple of snobs, anyway.”

“All the same,” said Nigel, “I do think he’s a bit unorthodox. He must be a gent with private means who sleuths for sleuthing’s sake.”

Angela and Nigel are told by another investigator: ‘”He has had an expensive education,” said Sumiloff quaintly. “He began in the Diplomatic Service, it was then I first met him. It was for private reasons that he became a policeman. It’s a remarkable story. Perhaps some day he will tell you.” I don’t think we ever do hear this story.

He does not like picking apart people’s lives: ‘”There are certain aspects of our job that are not very delicious”‘. We get quite a bit about his Wimsey-ish dislike of the accusation and arrest part of the case:

“Sorry! I’m a bundle of nerves at the moment, and I do so hate murders.”

“A policeman’s lot is not a happy one,” he said wryly. “This case has now reached a point which I invariably find almost intolerable.”

“You are an extraordinary creature,” said Nigel suddenly. “You struck me as being as sensitive as any of us just before you made the arrest. Your nerves seemed to be all anyhow. I should have said you hated the whole game. And now, an hour later, you utter inhuman platitudes about types. You are a rum ’un.”

Books mentioned

Holmes

Nigel is reading Conrad’s Suspense (1925)

The reason(s) why Alleyn doesn’t tell anyone who the murderer is before the big reveal

“It is not for the sake of keeping you on tenterhooks that I don’t answer that at once. I want someone to listen to the evidence. Oh, we’ve gone over it at the Yard ad infinitum, of course. There are one or two of us who know the case-book off by heart. But I want to hear myself repeating it to someone fresh. Will you be patient, Bathgate?”

“I am not going to tell you. Oh, believe me, Bathgate, not out of any desire to figure as the mysterious omnipotent detective. That would be impossibly vulgar. No. I am not telling you because there is still that bit of my brain that cannot quite accept the Q.E.D. of the theorem.”

Oddnesses

The scene with the third gardener’s small daughter is strange and I’m not sure what we are supposed to make of Alleyn’s initial lack of success with questioning the child and then his switch to charming her. Marsh overdoes the revulsion: “a very small, very dirty, very red-faced child of undecipherable sex … her barrel-like body … her filthy little face … a fat earthy paw”, not to speak of her father’s “unappetizing trousers”. I think on balance it’s a successful scene in showing both Alleyn floundering and the gap between the working class and upper class way of expressing themselves: ‘”Loidies don’t go wiv loidies in der coppus.” Stimson laughed coarsely. “Isn’t she a masterpiece, sir?”‘

The description of Marjorie dancing is overly deep: ‘There are some women who, when they dance, express a depth of feeling and of temperament that actually they do not possess. He [Nigel] saw that Mrs. Wilde was one of these women. Under the spell of that blatantly exotic measure she seemed to flower, to become significant and dangerous.’ Marsh doesn’t really do anything with these characteristics, having set them up.

Questions and things that I wish Marsh had developed in later books

Well, the “remarkable story” of why Alleyn joined the police, of course.

Alleyn’s cousin, Christina, who went to Newnham and is ‘”a fully fledged chemist now … and lives in an ultra-modern flat in Knightsbridge”‘. She needs her own series.

Why doesn’t Sir Hubert, who was a diplomat, recognise Alleyn from his own time in the Diplomatic Service?

Why and how does Sir Hubert have an “Assyrian gong” in apparently excellent and usable condition?

Why didn’t Rosamund Grant become a doctor? (In Alleyn’s words: ‘”She studied medicine at the university, clever girl, and intended to become a doctor”‘.)

Final thoughts and score

The Russian element doesn’t really work, I think. It might be more successful if Tokareff and Vassily were less broadly sketched. Indeed most of the characters could do with being more than a couple of adjectives. We don’t see Sir Hubert’s famous charm. Arthur Wilde is apparently a famous archaeologist but we don’t get any details of his work. There’s no sense of how anyone spends their time, except for Nigel’s journalism. Angela presumably has something to do with the housekeeping, but we don’t see that either. It feels as if Marsh has had the idea of death during the Murder Game and then put together a group of Bright Young Things, except most of them are not that young. The torture of Nigel by the Russians is an intrusive element which reminded me of the treatment of Ricky in the much later Last Ditch.

Much of Marsh’s style remains consistent across the series, though, and her exploration of Alleyn’s character in later books builds on this one. 3/5, with an extra element in there for being the start of the series, sine qua non.

Other reviews

A Penguin A Week disliked the tone.

My Reader’s Block found Alleyn not yet very interesting.

Pretty Terrible notes Marsh’s focus on the visual.

Clothes in Books says “It’s not a terrible story, but you would not have been betting on the author becoming a Queen of Crime and producing a considerable body of work”.

Bloody Murder looks at the adaptations of the book.

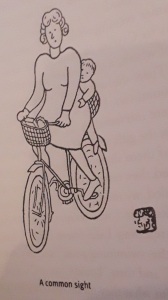

Chiang Yee, 1944.

… while strolling near Radcliffe Square. In the soft late spring air a haze of peaceful antiquity seemed to permeate the very stones of the buildings. The round dominating dome of the Camera in the centre; the St. Mary’s Spire; the dull yellow wall of Brasenose; the twin towers of All Souls’; the Bodleian; Hertford and Exeter Colleges – all seemed to be taking part in a solemn atmospheric ceremonial service. Two professors in long black gowns and mortar boards came out of Brasenose College , and added, as it were, a touch of human antiquity to the scene.

Yet there was a tinge of present-day atmosphere too: white-haired scholars in modern dress with books under thir arms; a few girl students in brightly coloured jumpers and long trousers were going in and out of the Camera building; an undergraduate in khaki , evidently undergoing some sort of military training; and two W.A.A.F.s who were examining the Camera. But these products of the new world, including, I suppose, my own flat face from modern China, blended harmoniously with the ancient buildings.

Chiang watches fencing in the grounds of New College, and “discovered, at the corner near the college wall, a group of green bamboo leaves nodding their leads to me in the wind. They must, I thought, have recognized my racial kinship with them!”. The book is largely about the natural world, the birds and flowers he sees in Oxford, especially those which remind him of China. He is at times, briefly and in passing, critical of the privilege of the Oxford establishment – the man who yells for salt in the Oxford Union, about whom Chiang says dryly, “undoubtedly an Oxford graduate who knew the place and the servant so well that formality was superfluous”.

The image of the woman and child on the bicycle reminds me of what my mother has told me about cycling in Summertown with me in the child seat – apparently I swayed and sang to myself. Having to make my own entertainment, clearly. The swaying sounds rather precarious.

The picture of Chiang having a hair cut is called Hair Raid because of what some children yell when the air raid siren goes off.

Chiang quotes a letter from Elizabeth Longford in which she tells him about her experiences as a student in Oxford:

I know I enjoyed being at college, though I complained a lot at the time, as one always complains when one is just growing up. It was pleasant to have comparative freedom, after being at school. I had a little room of my own (women in college have one room, men have two), and could stay up and talk all night to my friends and could read what books I liked, and did not have to go to lectures if I did not want to. Of course I wanted still more freedom than I had: I did not like being locked in at a certain hour; I wanted to read books quite unconnected with my studies; I did not like all the women students and professors in the college, and there were rules against seeing the men students! Those rules are mostly changed now, and anyway we broke them easily. I liked the country around Oxford and went for long walks and boating on the river, and made some friends, and there was plenty of leisure, and no trouble about housekeeping. My tutors were quite kind, and I enjoyed studying Greek and Roman literature and philosophy and history. You will have discovered that there are some learned professors in Oxford… I always preferred the ones who were old, and not at all interested in modern life, and not tidily dressed or even very clean! In those days, nobody was much interested in politics. I believe it has changed since; the students were more interested in literature and art, and we had little magazines which were very ambitious, and almost everybody tried to write poetry and short stories. We were also fond of the theatre, and there was a lot of amateur acting, which I’m afraid was very bad. Just occasionally when there were examinations, we became terrified and worked all night; but we spent most of our time talking and drinking tea and coffee. It was pleasant to meet foreign students, and there was a Chinese girl in my college who was much more amusing and clever than anyone. We decorated our rooms according to our own taste: I had some reproductions of French impressionist pictures, an imitation of a Byzantine ikon painted by a student of history, a Buddha, an Indian table-cloth, a plaster head of Alexander the Great which was much too big for the room, and as many brightly coloured cushions as I could collect, and a Persian rug. And we smoked Turkish and Russian and Egyptian cigarettes – which I don’t like any more and were not at all interested in food – which I am now…

Longford was at Lady Margaret Hall from 1926 to 1930.

Glyn Daniel, 1954.

Dedicated to Villiers David. Martin Edwards says that this was a friend of Daniel and a poet, painter and novelist.

This second mystery by the archaeologist Glyn Daniel is set in 1945 in the seaside village of Llanddewi in the Vale of Glamorgan.

Plot spoilers follow but I do not reveal the murderer.

It starts with a good set-piece village committee meeting, which reminded me of the WI meeting at the start of Marsh’s Grave Mistake and, as in that book, uses the first character to whom we are introduced as a device to tell us about others, and then rather drops that character – to my disappointment in both cases.

The vicar, who chairs the committee meetings, has “many committees over which … to preside – from committees to provide underwear for the starving children of Europe to protest meetings to prevent the Glamorgan County Council from constructing a coast road from Barry to Porthcawl”. This meeting is to arrange the Welcome Home for the men (and a couple of women) returning from the war. Each person will be given some money and there will be a gathering in the Village Hall. Only one man from the village was killed, and that was in a road accident. There is a discussion about whether to vary the amount given to each person by rank, as War Service gratuities were, but the vicar says that everyone should have an equal share. They go on to discuss which branches of the services should be included – for instance, “‘obviously we must include the doctor’s niece, who was in the W.A.A.F. But what about all the border-line cases – the Red Cross and the Land Army, and for that matter, the Home Guard.'” This leads to a snipe, “‘if we widen the scope of our welcome, we shall end up by welcoming back our conscientious objectors'”.

At this point, Daniel focusses on one person at the meeting: Evan Morgan, a self-made shop-keeper and shop-owner who has bought the Manor House. He has two sons – Rees, who was a conscientious objector for a while, and an illegitimate son, Mervyn, whom he prefers. Evan is planning to marry again. He is “handsome in an animal way, as you might say an ox was handsome, powerful and ruthless” (rather Cold Comfort Farmish).

After the meeting, the vicar and the schoolmaster, John Davies, discuss the death of the latter’s daughter, Daphne – without giving details. Davies suggests that it might have been murder. They also mention that anonymous letters have started again.

The Thomas brothers have a conversation because Joseph Thomas is planning to divorce his wife. She is having an affair with Morgan. “‘I remember the bastard when he was an errand boy. … He was a dirty, lucky twister then. He’s a twister now. I hate him.'”

Morgan tells his long-term mistress, Ellen Williams, that he is planning to marry a much younger woman, Janet Anderson. Ellen is angry and afraid, and reminds him that one of the men coming back from the war, Bryn Davies, had been “‘practically engaged'” to Janet before the war. She says that Bryn may also be angry that Morgan had an affair with Bryn’s sister, Daphne.

We then get a brief scene with Bryn Davies and the vicar’s son, David Morris, who are in Basrah in the Persian Gulf on their way home. They also talk about Daphne’s death. David had hoped to marry her. Bryn says

Daphne was a fine kid. A chap couldn’t have had a finer sister. It makes me sick sometimes to think of the things we did together, that we can never do again, like walking along the cliffs to St. David’s Castle in the teeth of a September gale, the wind almost tearing our hair out by the roots; and picking blackberries in the Castle ditches; and walking at night over to Cowbridge; and collecting mushrooms from the meadows behind the church.

There is an odd and rather revolting reference to the “jig-jig wallahs” who provide women for “the sahib in transit”.

Back to South Wales. Mervyn, Morgan’s illegitimate son, and his mother, Ellen, talk about whether they can prevent Morgan from marrying Janet.

John Davies talks to the doctor about his (John’s) wife, Ruth. The doctor tells him she is dying of cancer and has about three months to live. They agree not to tell Ruth this, or the truth about Daphne’s death. However, Ruth tells the doctor she knows both that she is dying and that Daphne’s death was the result of an illegal abortion. She says that the only people to whom capital punishment is not a deterrent “‘are those already sentenced to death'”.

We are finally introduced to the book’s amateur detective, Sir Richard Cherrington, an archaeologist and fellow of a Cambridge college. He has just completed “a corpus of the Bronze Age statues of the West Mediterranean”. He thinks

scholarship was just another animal pleasure. Curiosity and the urge to collect. It was the squirrel collecting nuts, the small boy collecting stamps. What difference from the scholar collecting bronze statues? It might all be a form of constipation. But did the squirrel arrange the nuts in new patterns? Did the small boy deduce any new facts from his stamps? Cherrington sighed. True; but what was the difference? “Only one of degree,” he said firmly and out loud, addressing his large cat, Voltaire, who sat on a pile of towels on a table by the window, visually in contact with her master, but sufficiently far away to avoid being splashed by his bath-water. Voltaire purred, not because he had understood Sir Richard’s remark, nor because he found his tall, naked, slightly bellied form attractive, but because it was breakfast-time. Cherrington’s gyp had brought in the breakfast dishes from the kitchen; Voltaire sniffed at the covers by the fireplace and hoped for kidneys.

Cherrington seized a silver dredger of talcum powder and drowned himself in a shower of white mist. The fine particles drifted over to the window and irritated Voltaire, who jumped down and walked leisurely through the bedroom and back into Sir Richard’s big keeping-room. He gave the breakfast dishes another olfactory examination and was disappointed; a second smelling suggested that they were, perhaps, only sausages, and post-war, bread-filled sausages did not take a high place in Voltaire’s estimation.

(Cat changes from female to male in this section.)

Sir Richard’s aunt lives in Llanddewi and has written to ask him to visit to advise her about the anonymous letters. She says she knows the writer. She offers as inducement a goose and burgundy and claret. Sir Richard agrees, and turns up by car blowing “all his car horns – the ordinary klaxon for the English roads, the cuckoo horn which made him so popular with his colleagues’ children, and the special mocking trumpets he kept for motoring in France”. His aunt has two cats, “‘The fat gentleman who belches is Sir Toby, and the thin female who moans and groans so much in her sleep is Lady Macbeth'”. Sir Richard “tickled the cats with the practised skill of a cat-loving bachelor”.

This, the first quarter of the book, is set-up. Following this, Morgan is found stabbed. His body is discovered by David Morris and Bryn Davies, who are then attacked by the murderer, whom they can’t identify. The Chief Constable, who is an amateur archaeologist and respects Sir Richard, allows him to be involved in the investigation. There is much back and forth and interviews with suspects – these include Mervyn and Rees Morgan, Joseph Thomas, Ben Anderson (Janet’s father – motive, to prevent the marriage) and Ellen Williams as well as Davies and Morris. There is a lot of evidence about times in a Freeman Wills Croftish way; the clock kept fast in the pub, the time of the madrigal concert on the Third Programme. There is another death.

Eventually – and it does feel rather long in coming – Sir Richard and his aunt give a dinner for the police in order to explain to them what happened. “He warmed to his theme as he went along, and his left hand occasionally twitched at the hem of a non-existent black gown.” His aunt serves the goose, “an excellent timbale maison with quenelles, mushrooms, and crawfish … followed by an equally good cheese soufflé”. They have Chablis and Richebourg 1929 to drink; the local Inspector is rather tipsy “and would have loved a glass of water, but thought it would be rude to ask for it”. The Scotland Yard Detective Inspector “had been longing for a pint of beer all through the evening”. Sir Richard says of the young men who are suspects that “‘in the immediate post-war period of any man’s life anything is possible. I remember only too clearly in my own life the years 1918-19′”. His views about the murders change as he talks and as the others have some input. He “stood up with his back to the fire, a brandy glass in his hand. The faces of the Chief Constable and Inspector Colwall registered their surprise. ‘God, what a slow-witted fool I have been!’ said Sir Richard. ‘I see at last how the murder was done … ‘”

Sir Richard feels sorry for the murderer and his family. After the arrest, Sir Richard goes to the Dordogne to try to escape “from the intricate emotions of other people’s lives into which he had stepped”. An old friend, a Sûreté officer, asks him for help with an investigation in France, and Sir Richard eventually agrees. “And that night for the first time his dreams were not disturbed by memories of Llanddewi.”

There is not enough archaeology in the book. Early on, we hear about the Chief Constable’s passion for archaeology:

He had made it his aim to visit every antiquity in South Wales, and with tireless enthusiasm he drove around the countryside in a shooting brake equipped with camera, surveying instruments, field-glasses, six-inch maps and air photographs [which I would think he’d have had problems getting hold of during the war, not to speak of the petrol issue, so presumably in the thirties], tracking down every earthwork, every barrow, every vestige of a prehistoric field-wall or village, resolutely exploring every clue in field or place-name which might conceal the presence of an antiquity. Queer chap, the hunting-fishing fraternity said when they discussed him in the lounge of the County Club in Cardiff. A good chap, of course – but strange. And they put it down to the Indian sun.

David Morris, the vicar’s son, collected fossils as a child. “Lovingly he picked up the finest ammonite in his collection. What a find that had been – on a ledge of rock just washed by the sea in the cove at Sealands Farm. What a labour of love it had been chipping it out of the soft limestone, hurrying lest he should be cut off by the rising tide, yet careful not to break the corrugated ribbings of the tight, spiral shell.” – nice lyrical bit of writing.

There are a couple of references to the past of the village. The vicar, in the cemetery, thinks about “the first Christian burials of Welsh people on this spot long before the Normans had come. And before that – on the hill, by the Vicarage was a barrow with burials supposed to be as much before the Christian era as the present moment was after it”. There are also references to the village people being Mediterranean. Sir Richard thinks that Rees Morgan is “as good a representative of the Mediterranean race as one could expect to find in Wales after centuries of racial mixture”, and that the village is “straggling up the opposite hill like a small Mediterranean township”.

The village of Llanddewi may be based on Llantwit Major, also in the Vale of Glamorgan, where Daniel grew up. Daniel himself would have been about 31 at the time the book is set (born in 1914), younger than Sir Richard, who must have been fiftyish or older. Daniel was posted to Delhi in the war to lead the Central Photographic Interpretation Section. His obituary in American Antiquity says that Sir Richard was based on Mortimer Wheeler. The same obit also says that Daniel himself had an attachment to the Dordogne and to its food and wine; he and his wife had a second home there. It mentions as a positive thing his nurturing of the “Johnian Connexion”, the archaeologists linked to St John’s, Cambridge, who “came to monopolize most of the senior positions in British academic archaeology”; the sort of thing which gives me weary rage.

The book is too bleak for me. I had some difficulty telling all the men apart, and I don’t especially like the Croft school of detection. There are so many deaths by the end and so pointless – the car accident, the abortion, Ruth Davies’s cancer and so on. The murder may solve a problem in the village, but the detection of the murder does not have a similar healing aspect. Also, we never see the Welcome Home party, which seems a shame.

Martin Edwards, in the link at the start of this post, shows an image of a letter Daniel sent to Villers David with the book, in which he says that he tried to write a novel in which the reader would sympathise with the murderer, but that he failed both to write a good detective story or to get the reader’s sympathy.

There is also a review of the novel at Cross-Examining Crime.