Elizabeth of the Garret Theatre is by Gwendoline Courtney, nd but 1964.

Backstage with Peggy is by Doris A Pocock, nd and not in Bodleian or BL catalogues, but Goodreads says it’s 1950. This sounds about right as there is a suggestion that sugar is rationed.

I got these in one batch from Oxfam, and they are similar enough that it seems a good idea to review them together. I think they probably belonged to the same person (same first name in both books). Here are the covers:

I’ve read quite a few of the other books listed. Katherine at Feather Ghyll was an online recommendation and Rhodesian Adventure a recommendation from my mother when I wrote an article about children’s books of the 50s and 60s.

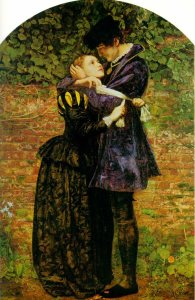

Elizabeth isn’t illustrated. Here are the pictures from Peggy, starting with the frontispiece:

Of the two, I think Peggy is slightly the more interesting book. Elizabeth has some lively characters, but the detail of Peggy, such as getting the Scouts to make arrows for props (the school dramatic society is putting on “Robin Hood”) makes it more gripping for me.

The (beloved) father in Elizabeth has unfortunate views about girls’ education (unfortunate to me – Pocock obviously supports him). It’s just to make sure they don’t look stupid. “‘General culture will be of far more use to you than a deep knowledge of higher mathematics or Greek,’ he once told Alison and Elizabeth. ‘If you know something of most subjects you will never appear a fool – as long as you’ve enough intelligence to realise just how little you know.'” Let’s hope his daughters don’t want to specialise in maths or Greek.

The conflict and resolution in both books works out predictably, though I did feel a bit sorry for Elizabeth and her sisters, taken in hand by their (thoughtful and caring) stepmother. Even their best friend, the Rector’s son, is critical of their previously chaotic home life: “Fond though he was of the family, he had for some time agreed with his father that it was time something was done to take the girls in hand. The kind of careless gypsy life they were leading might not have mattered so much while they were younger, but it was time Alison and Elizabeth and even Susan began to alter their ideas a little.” There’s more than a whiff of male disapproval that the girls aren’t fitting themselves to take women’s roles here.

The plot of Peggy follows the usual self-sacrifice route. You can see why Lawrie in Antonia Forest’s The Cricket Term (1974) assumes that if she gives up her part in the school play, good things will happen – it’s a well-trodden route. The character of Veronica, film-star’s daughter, was reasonably subtly done, I thought, with the book’s disapproval of her “shallowness” presented alongside her charm and her real affection for her great-aunts, whom she treats selfishly.

I liked everyone’s excitement about the first night bouquet “done up professionally in Cellophane paper” and evidently from Interflora or the like: “‘haven’t you seen those advertisements, “Say It With Flowers”?'”.

In both books the main characters end up planning a theatrical career. Elizabeth is evidently destined for greatness as a Shakespearian actor, but I liked the fact that Peggy’s thinking of her career in much more low key terms:

” … Even while I’m building castles in the air (as of course anybody would) and imagining myself a Hollywood star with an enormous fan-mail and a fabulous salary, a mocking little imp at the back of my brain keeps on insisting that that sort of thing is for Veronica Cheviot, not for me … I’m more than likely to end up as nothing more exciting than a teacher of elocution or something of that sort.” … ” … one little success in a school play … isn’t enough to found a brilliant stage career on! But the funny thing is, Kath, I don’t feel as if I should mind so very much if it did all end in having to do something quite ordinary. It isn’t only the stars who get the fun. … I could be quite happy … getting on with whatever was my job – only I somehow feel I should like it to be a job somehow connected with the stage. … “

Doris Pocock also wrote Lorna on the Land, which I enjoyed.

![landseer-1870-antique-hand-col-print.-the-stag-at-bay-[2]-38592-p](https://booksandpictures.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/landseer-1870-antique-hand-col-print-the-stag-at-bay-2-38592-p.jpg?w=300&h=225)